Home -> Danton Case -> September/October/November Archives

|

|

|

The Mike Danton Murder-For-Hire Case - September, October and November Archives

In April of 2004, Mike Danton (or Mike Jefferson, depending on who you speak to) and 19-year-old Katie Wolfmeyer were arrested and charged with hiring a hit man to kill Mike's agent, David Frost. News reports didn't admit to Frost being the alleged target at first, but as more and more details surfaced, the more obvious it became.

The reason I'm choosing to archive this story on this site is because the parallels between this case and Sheldon's were too similar to be passed off. Not only that, but in the days following the arrest, Sheldon's name was mentioned twice in two different posts on two different boards. So I did a little research, and decided that details about the case should be posted here.

Following are the September, October and November, 2004 articles regarding the case.

Wolfmeyer Pleads Ignorance in Murder-For-Hire Plot (9/16/04)

Wolfmeyer Acquitted in Murder-For-Hire Plot (9/20/04)

Danton's Sentencing Pushed Back (10/19/04)

Wolfmeyer pleads ignorance in

murder-for-hire plot

WebPosted Thu Sep 16 15:50:39 2004

CBC SPORTS ONLINE - Katie Wolfmeyer testified Thursday at her conspiracy

trial that she knew nothing about NHLer Mike Danton's plan to murder

his agent or anyone else.

The 19-year-old said she was unaware that Danton, with whom she briefly

dated, and her acquaintance, Justin Levi Jones, agreed to a plot for

Jones to kill someone at Danton's apartment for $10,000 US.

Katie Wolfmeyer walks into federal court for her murder-for-hire trial

in East St. Louis, Ill., Thursday. Wolfmeyer is expected to take the

stand in her own defense.

The alleged target was Danton's long-time agent, David Frost.

"Danton didn't tell me anything," she testified in U.S. District

Court. "It was between Levi and Danton. I knew nothing. I knew

absolutely nothing.

"The words murder or kill were never, ever said to me until I talked

to the FBI," said Wolfmeyer, who is facing federal charges of conspiring

to arrange a murder for hire and using a telephone across state lines

to arrange it.

Jurors will decide if Wolfmeyer was a willing participant in the scheme

or a naive victim manipulated by Danton. Jones is a police dispatcher

from Columbia, Ill. He pretended to Danton that he'd act as a hit man,

while actually recording conversations for the FBI. In earlier testimony,

Jones said Wolfmeyer knew that Danton wanted someone dead and continued

to take part in the plan.

Wolfmeyer, wearing a purple sweater and matching bow in her ponytail,

told the court she didn't know the difference between a police officer

and a police dispatcher, and she thought perhaps Jones was providing

security help for Danton.

Danton, a 23-year-old native of Brampton, Ont., had told Wolfmeyer someone

was after him, and she handed Jones the phone after Danton asked her

if she knew someone who would do anything for $10,000. She said she

agreed to go with Jones to give him directions to Danton's apartment.

"I thought Levi was going to go over there and check on the apartment,

make sure nobody was over there," she said.

Earlier in the trial, an FBI agent, Emmerson Buie Jr., testified that

Wolfmeyer gave a statement when she was arrested April 15, saying that

she thought Danton wanted someone beaten up. She said he misunderstood

her.

While still in custody the next day, she changed her statement to another

agent, Melanie Jimenez. Jimenez said Wolfmeyer told her it had "clicked"

in Wolfmeyer's mind before the alleged hit that Danton wanted someone

killed.

"I did not write that. It's Melanie's words. It's not my words,"

Wolfmeyer said, but confirmed she had signed the statement.

Authorities said Danton and Frost had argued over the player's "promiscuity

and use of alcohol and Danton allegedly feared Frost would talk to Blues

management and ruin his career.

Danton has already pleaded guilty and faces sentencing Oct. 22. Judge

William Stiehl has ruled that Danton does not have to testify against

Wolfmeyer.

Frost has publicly denied he was the target of the alleged murder scheme.

From CBC.ca

Wolfmeyer acquitted in murder-for-hire

plot

WebPosted Mon, 20 Sep 2004 18:12:41 EDT

CBC SPORTS ONLINE - A Missouri woman was acquitted of charges she helped

former NHL player Mike Danton hire a hit man in a failed plot to kill

his agent. A federal jury in East St. Louis, Ill.. deliberated for more

than three hours before clearing 19-year-old Katie Wolfmeyer of two

felony counts of conspiring and using a telephone across state lines

to organize a murder.

"I knew all along that I was innocent," Wolfmeyer said. "Our

interest as prosecutors at any trial is to ensure the evidence is fairly

and effectively put before the jury," said U.S. Attorney Ron Tenpas.

"We respect the jury's verdict." Danton, who pleaded guilty

of conspiracy charges in July, is expected to be sentenced on Oct. 22.

He did not testify during Wolfmeyer's trial. Gasps of relief could be

heard from Wolfmeyer's family and friends when the acquittals were announced

in the courtroom. Wolfmeyer and her mother cried.

"I'm glad the jury saw through all that," Wolfmeyer said.

In his closing statement, Wolfmeyer's lawyer Donald Groshong portrayed

his client as a unwitting participant in the murder-for-hire plot. "We're

not asking you for sympathy," he said. "Katie Wolfmeyer never

intended to murder, never intended to be involved in a murder, never

intended to have one committed."

Before Groshong addressed jurors, assistant U.S. attorney Stephen Clark

told the courtroom to look past Wolfmeyer's sobbing testimony. Wolfmeyer

claimed the FBI plotted against her. "This is no conspiracy against

Little Miss Muffet," he said. "She's tried to play on your

sympathies."

Prosecutors claimed that Wolfmeyer put Danton in touch with acquaintance

Justin Levi Jones, who was offered $10,000 US to kill Danton's agent,

David Frost. Jones, a police dispatcher from Columbia, Ill., pretended

to accept Danton's offer, but recorded his conversations with the FBI.

Wolfmeyer claimed she did not know Danton's intentions.

"Danton didn't tell me anything," she testified. "I knew

nothing. I know absolutely nothing." In earlier testimony, Jones

said Wolfmeyer knew that Danton wanted someone dead and continued to

take part in the plan. Wolfmeyer told the court she didn't know the

difference between a police officer and a police dispatcher, and she

thought perhaps Jones was providing security help for Danton.

With files from Canadian Press

From CBC.ca

Easy Prey

By Gare Joyce and Bruce Feldman

For ESPN Magazine

10/11/2004

Mike Danton always thought that the worst thing that could ever happen to him was not making it to the NHL. He was wrong.

The teenage girl with the purple ribbon in her hair was still waiting for the man with the gun to show. The plan was that they would rendezvous at Denny’s parking lot at 10 PM. The man called her cell phone at 10:15 to say he was running late, he’d be there soon, and hung up. In fact, he still had to pick up the gun.

By 10:30 PM last April 15, Katie Wolfmeyer, a 19-year-old nursing student who’d never had so much as a parking ticket, and Justin Levi Jones, the 19-year-old gunman, were making the short drive to a townhouse-style apartment complex in Brentwood, an upscale St. Louis suburb. Jones told the guard at the gate that they wanted to see Mike Danton. They knew that Danton, a 23-year-old wing with the St. Louis Blues, wouldn’t be home. He was with his teammates in San Jose, trying to overcome a 3-1 series deficit in a first-round playoff matchup with the Sharks. Two nights earlier, Danton – a guy whose grit and edge made up for his lack of size and skill – had scored his first postseason goal, in a loss.

The security guard called Danton’s apartment, and a chubby man in his mid-30’s appeared at the second floor railing. He yelled down, asking Jones who he was; Jones got nervous and gave a false name. When the chubby guy said he was Danton’s father, Jones drove away. But the man on the railing, who was actually Danton’s agent, David Frost, was unsettled by this unexpected guest. He called his client in San Jose. Then, after talking with Danton, he called the police and began babbling. He said he’d known Danton for years… that Danton had given him a key to the apartment… that Danton had begged him not to go to Blues’ management and ruin his career … that he had threatened to leave Danton.

Meanwhile, another call was taking place, this one between Danton and Jones, the man the player had hired to make the hit. Danton told Jones that if he got picked up by the police, he should say he didn’t know Danton, that he had accompanied Wolfmeyer to her boyfriend’s apartment because she was uncomfortable going alone. “This is the only way we can both get out of this,” Danton said.

But there was no way out. At 12:30 AM, FBI agents arrested Wolfmeyer on the charge of conspiracy to commit murder for hire, after the distraught student signed a confession. Investigators retrieved three messages Danton had left on Wolfmeyer’s cell phone between 12:26 and 12:33 AM, instructing her what to tell police. With written consent from Danton’s “father,” agents searched his apartment. They found, just as the alleged gunman told them they would, $3,000 in an unlocked safe in Danton’s closet – the down payment for the hit. On the morning of April 16, hours after the team was eliminated from the playoffs, Danton was arrested in San Jose on the same charge as Wolfmeyer. He’s been sitting in a jail cell ever since.

It all began eight years ago, when Mike Danton was still know as Mike Jefferson, in a place a long way from St. Louis, the kind of place where living on the edge is a short drop into an abyss. The edge in this case was room 22 at the Bay View Inn, in Deseronto, Ontario. And if you had gone there and peeked inside, you would have caught a glimpse of the dark world that Mike Danton entered and never escaped from.

You can’t see the Bay of Quinte from the Bay View Inn. In fact, all you can see, other than the highway out of Deseronto, is a gas station and a rope factory, the main source of employment in this town of 1,900 located next to a Mohawk reserve. Even the waterfront isn’t very scenic. Out-of-towners, few and far between, head to the vineyards and sand dunes in the neighboring county. Fishermen blow in during the season; road crews show up for summer repairs. That’s about it. There’s no pool at the Bay View, no health club, only the lingering smell of cigarette smoke and spilled beer floating up from the diner and bar on the main floor. The place is made up of convenience suites, with kitchenettes and fold-out sofa beds in living rooms.

It’s not the sort of home away from home that parents envision for their kids. Steve and Sue Jefferson say they never imagined their son spending his nights in a place like that. They were just letting Mike pursue his dream. Sending a boy off to another town to play hockey in a better league is a rite of passage for Canadians, a source of pride. That’s what Walter and Phyllis Gretzky felt when they sent 14-year-old Wayne from Brantford to Toronto. Same with Barney and Rose Tootoo, when 14-year-old Jordin left their Arctic Circle town of Rankin Inlet for Edmonton. It’s why Steve and Sue Jefferson sent Mike from Brampton, Ontario, to Deseronto in the fall of 1996. Like all the others, they say, they were hoping, trusting, he’d live with a good family and eat good meals and develop into the kind of player who’d have a good NHL career.

And Mike Jefferson was good, a grinder who never quit. But coming up on his 16th birthday, he was at a crossroads. He’d come off a championship season with the Young Nats in Toronto, a program that produced Eric Lindros, Adam Graves and dozens more NHLers. Mike was a small, scrappy kid. He needed to keep improving, to find tougher competition. He needed to grow up as a player, to go from a league for boys to a league for men.

He needed to go to Deseronto, David Frost told him. Frost was 29, another Brampton guy. He claimed to have competed in high juniors, but at least one of his former players says, “I don’t think he ever played – he couldn’t even skate.” Frost had been Mike’s coach with the Young Nats, but his undisciplined behavior got him fired. His teams brawled constantly, and during one locker room rant, he reportedly dumped a garbage can over a player’s head. Despite his rep, the Quinte Hawks offered him an assistant’s job. It was just about the last stop for a guy who’d also been accused of serving booze to 14-year-olds. “He’d run out of places where he could coach,” says John Gardner, president of Toronto’s minor hockey association.

Frost told Mike that Quinte was the perfect step up for him, the same thing he told Mike’s best friend and teammate, Sheldon Keefe (now with the Phoenix Coyotes). The two told anyone who would listen that they would make the NHL someday. Now here was a chance to turn a dream into a reality – and for Mike to escape a nightmare. He hated Brampton, his rundown house, the broken vending machines and catering trucks (his parents worked in the food service business) parked in front. There was another reason, say sources close to the family. “He just hated his father,” says former classmate Matthew Plastow. “He was embarrassed by his drinking.” But whether Mike was breaking away from a dysfunctional home – a characterization Steve rejects – or the Jeffersons were just supporting their son’s career path, the end result was the same. Mike told his parents he was leaving, and they let him go.

Frost quickly put his stamp on the Hawks. Fights started in warm-ups and continued in the arena hallways. The fans loved it. The players might as well have been rock stars. The first-year franchise, with the youngest lineup in the league, reeled off 20 straight wins in one stretch. “We had Frosty to thank for that team,” says arena manager Dennis Vick. “He made those players what they were.”

But the show had its troubling side. Elena Philips, the retired nurse who welcomed Jefferson into her home, sensed something wrong about this team right from the start. It wasn’t so much the hazing stories she heard – a bunch of boys crawling around a room on their knees, naked, marshmallows in their butts. No, Philips was worried about Mike spending so much time with his coach in Room 22 at the Bay View Inn.

Frost had checked into the motel with three of his players from Brampton: Keefe, 16; Larry Barron, 20; and Darryl Tiveron, 21. Around Deseronto, Room 22 soon developed a reputation as party central. Local girls – “puck bunnies” – dropped by all the time. When the manager imposed a 10PM curfew, they climbed in the second-story window. “Frost told me, ‘Don’t worry about Mike, he’s having lots of sex,’” Steve Jefferson says. “I asked him how he knew, and he said, ‘I’m right beside him.’”

“We heard all about stuff going on at the motel,” says one former Hawk who didn’t participate. “At the time I didn’t think it was anything unusual. Now I look at it, and a 30-year-old coach was partying with 16- and 17-year-old guys and girls in the room. Yeah, that seems weird.”

Eventually, word got back to some of the parents. Deseronto police Chief Norm Clark says that he and head coach Greg Royce, who had lost control of the team, expressed their concerns to the Jeffersons and Keefes, but the parents were too caught up in their sons’ dreams to hear it. Adds John Boultbee, a former Hawks assistant, “Greg told Steve Jefferson he was worried about what was going on, and Steve told him, “You’re not the one who knows hockey. Mind your own f---ing business.’” But things came undone when Frost sucker-punched Tiveron on the bench during a game (punishment for playing soft). Town cops saw it and charged him with assault. Frost was suspended by the league and pleaded guilty in court. The Hawks faded in the playoffs. “The guys who were tight with Frost just quit on the team,” says one player.

That effectively finished Frost’s coaching career, but it didn’t end his ties with Danton. From 1997 to 2000, the player bounced around the OHL, from the Sarnia Sting to the St. Mike’s Majors in Toronto to the Barrie Colts. Frost was a constant presence at every stop. In Sarnia, he would follow Mike back to his room and spend hours with him behind closed doors. At Mike’s games, he sat in the stands, giving “his kids” hand signals, positioning them on faceoffs. One GM called him a lunatic. But Steve Jefferson was still talking like he had faith in Frost, telling the Toronto Sun that Frost “was the best thing to ever happen to my kid.”

Mike was on the cusp of the NHL, and he was desperate to make the leap. The scrawny kid had turned himself into a buff bruiser, but most teams were scared off by his past. “Our sports psychologist talked to him before the draft,” says one scout. “We heard all the anger about his family. We knew about his association with Frost. We didn’t want anything to do with him.” But New Jersey did, taking Jefferson in the fifth round of the 2000 draft. Though the image-conscious Devils seemed an unlikely fit, they were impressed with his grit – if not his agent. By that time, Frost had been certified by the NHLPA, and his two clients were Jefferson and Keefe, Tampa’s 1999 second-round draft choice.

The Jeffersons had gradually lost touch with their older son. “The Mike we knew never really came back [from Deseronto],” Steve says. “We lost him there.” That’s why it was such a surprise when, in the summer of 2000, Mike invited his 13-year-old brother, Tom, to Frost’s cottage near Kingston, 150 miles east of Toronto. Tom had grown up from tag-along little bro into a legitimate prospect – a bigger, tougher version of Mike at the same age. Their parents figured the time at Frost’s cottage would give the boys a chance to get close again. But looking back now, they’re convinced Frost planned to recruit Tom, to steal away their younger son like he’d done with Mike.

One night, Tom called home from the cottage. “He told me that he’d been assaulted, tied up to a bed frame naked, had a gun pointed at him,” Steve says. “He was terrified.” Steve phoned the Ontario Provincial Police. They went to the cabin, but Frost and the others there – including Mike – gave conflicting accounts of what happened. An investigation ensued, and a photograph of Tom tied up was discovered, but no charges were filed.

While stories about Frost and his Quinte Hawks are disturbing, they’re not surprising to those familiar with hockey culture. In the 1980’s, there were whispers about juniors coach Graham James making unwanted advances toward players (he pleaded guilty in 1997 to sexually abusing two players), but everybody looked the other way at the time. Why? Nobody wanted to hear about it. “Hockey tolerates or encourages deviant behavior more than other sports,” says Dr. Cal Botterill, a sports psychologist and former pro player. “It’s worst below junior hockey. Sexual humiliation enforces a code of silence. Go to the authorities, and you’re a victim again. It takes courage to reach out.”

Steve and Sue Jefferson say that Mike broke off all contact with the family after the cottage incident. In July, 2002, he legally changed his name to Mike Danton, taking the first name of a kid he’d met at hockey camp. The Jeffersons found out about it the way everyone else did – in the sports section. Meanwhile, Mike’s career was stalled. He left the Devils during his second season over a dispute about an injury he said he suffered in training camp. GM Lou Lamoriello wanted to send him to the minors, but Danton refused, instead moving to California to live with Frost for three months. The player earned a place in Jersey lore by proclaiming that he “wasn’t drinking Lou’s Kool-Aid.” Although the Devils took him back, he played just 19 games over three seasons before being traded to St. Louis.

Danton skated on the Blues’ fourth line last season, going harder than ever. He was, in coach-speak, a high-energy guy: in 68 games, he scored seven goals while piling up 141 penalty minutes. He enjoyed St. Louis, the organization and the city’s nightlife. In fact, he had discovered quite a bit of Deseronto in the Gateway to the West.

One day, following a Blues practice at the Ice Zone, Danton introduced himself to a tall blonde named Katie Wolfmeyer, a rink employee – but no puck bunny. She was a standout volleyball player on scholarship at a local community college, an honor student studying nursing while juggling three jobs. “Katie’s the last girl you’d ever expect to get into trouble,” says one of her teachers at Central High. Most around the Ice Zone knew about Danton’s party boy rep and his fondness for strippers. But he was also a charmer. “Nicest guy on the team,” says one Zone regular. It wasn’t long before Katie was smitten. The bond was strengthened when Danton – in the midst of his first playoff run – broke down and let her know he was living in fear. Someone, he told her, was out to get him. Someone was coming from Canada to kill him.

That call came on April 14, while she was driving around with some friends. Katie asked them if anybody knew someone who would do anything for a friend. One of the people in the car said yes. He was Levi Jones, whom Wolfmeyer had met just hours earlier. Jones had done a two-semester internship with the local police during his senior year of high school before moving on to answering phones as a part-time dispatcher for a tiny western Illinois PD. He dreamed of joining the FBI, and spun tales to impress the girls. Although Jones told Katie he was interested, he didn’t know what was actually going down until Katie handed him the phone. Jones says Danton told him a Canadian hitman was coming to kill him over a debt. He then allegedly offered Jones $10,000 to kill the hitman. Jones said he’d need more details and gave Danton his number.

Danton dialed Jones (who was recording the call) at 12:02 AM on April 15. He told Jones that Wolfmeyer would take him to the apartment, and that Jones should make it look like he had killed a robber. Danton said the police could be led to believe that there were actually two burglars, and that one had killed the other in an argument. Throughout the conversation, Danton kept asking if there was any way Jones could do the job that night. “I’m pretty much begging,” he said. “I wouldn’t resprt to this if it wasn’t a matter of life and death.” Jones, now scared and realizing that Danton was dead serious, contacted the FBI. He was told to pretend to go along with the plot.

What had driven Danton to such a fragile state? Federal prosecutors say he was afraid of Frost. The criminal complaint said Danton was trying to kill a male acquaintance with whom he had faught over Danton’s “promiscuity and use of alcohol,” and that Danton feared the man would ruin his career. In the early morning hours of April 16, the FBI recorded a conversation between Frost and Danton, in which Danton tearfully explained he ordered the killing because he felt his agent was “going to leave him.”

When the story broke after Danton’s arrest, few people outside of the NHL had ever heard of him. But that all changed, due in some part to the ambiguous language in the FBI’s affidavit: acquaintance… promiscuity… threatened to leave Danton… ruin his career… backed into a corner… have him murdered.

Suddenly, Mike Danton was the lead character in a reality show directed by the Coen Brothers. Canadian papers ran headlines like “NHLer Charged in Gay-Slay Plot.” Outsports.com’s message boards crackled – finally, an outed gay man playing in a major sport. Teammates didn’t know what to think. Veteran Doug Weight said what Danton did in his personal life was his own business: “Let’s preface it by saying who knows what the situation is. There are rumors of what went on and who exactly was involved in this so-called thing.”

On May 21, Danton sat in an East St. Louis courthouse for his bond hearing. On that day, FBI agent John Jimenez testified that Danton’s road roommate, Ryan Johnson, had described the relationship between Frost and Danton as “strange and bizarre,” and that investigators had interviewed two other witnesses who said Danton tried to hire them to kill Frost six months earlier. The judge listened to three of 79 recorded conversations between Frost and Danton as they discussed an insanity defense. “It’s not an option to go to court,” Frost implored. “If we go to court, you are f---ing done. Are we clear? There is one way and one way only, and that’s psychiatric treatment. Because you really do need it.”

Later that summer, Sue Jefferson mailed Mike a note saying she hoped the ordeal would bring the family back together again. He sent it back to her torn to shreds.

“The truth is all going to come out eventually,” Frost says now. After three months of unreturned phone calls, he has called to say his public image is all wrong. He’s still Danton’s friend and always will be. He’s no Svengali, just a coach who made mistakes and had to reinvent himself as an agent to stay in the game. He denies he was the murder target. He says Danton is innocent of the charges he pleaded guilty to in July. Above all, he insists he never preyed upon or exploited Danton. His client just has some serious problems.

“Mike is bipolar,” Frost claims. “He has a borderline personality disorder: Big Mike and Little Mike. Big Mike can function in a lot of situations, but he reverts to Little Mike – emotionally needy, helpless – when he’s alone. It’s when he’s Little Mike that he has problems. Mike is delusional. He sees things that aren’t there. I was with him one night when he was driving home from the arena after a game [last spring]. He was taking all these side streets, going out of his way. He said, ‘He’s following me.’ I said, ‘Who?’ And he said, ‘My father.’ His father had never come down to St. Louis, but Mike was sure he was there.

“The Feds know he shouldn’t be going to jail, that he needs help. We wanted this to go to court. We think we would have won. But he had to think about what he was looking at if he lost. I’ve been accused of being a manipulator, but what are Scotty Bowman and Pat Burns and Mike Keenan? They’re all manipulators. That’s what a coach is supposed to do.”

It’s October, what should be hockey season, and almost everything about it feels wrong. The players are locked out, the NHL’s future is in jeopardy and two of its brightest stars – Todd Bertuzzi and Dany Heatley – are awaiting trial. We should be talking about Tampa’s chances of repeating. Instead, the only news on the horizon is the ending of this sad, twisted story about these sad, twisted people. Danton will be sentenced on October 22, and is looking at seven to ten years in prison. Wolfmeyer’s trial ended in acquittal. (One of the jurors said Wolfmeyer was “not innocent by any means of everything she’s done, but prosecutors didn’t present evidence to prove she was guilty.”) Jones has enlisted in the Navy and will soon begin basic training.

In Deseronto this summer, the provincial police questioned locals about David Frost and his time there. At least two women are said to have come forward with sexual-exploitation complaints dating back to his season with the Hawks. (Frost maintains he’s innocent and no charges have been filed.) Detectives from the small-business division were also looking into the team’s financial dealings.

Meanwhile, back in Brampton, a familiar rite of fall has already played out. In September, Steve and Sue Jefferson sent 17-year-old Tom off to Windsor, to play for the OHL’s Spitfires.

It’s that first big step

toward making his dream come true.

From ESPN Magazine

Danton's sentencing date pushed

back

WebPosted Tue Oct 19 12:44:02 2004

CBC SPORTS ONLINE - St. Louis Blues forward Mike Danton has had his

sentencing date in a federal murder-for-hire case delayed until November.

Friday's scheduled hearing has been pushed back to Nov. 8 due to a conflict

in the schedule of U.S. District Judge William D. Stiehl, the judge

hearing the case.

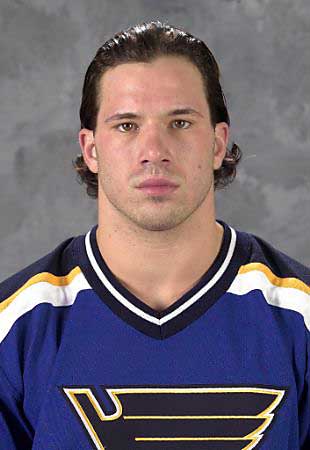

Mike Danton had his sentencing case delayed until Nov. 8.

Danton, a 23-year-old native of Brampton, Ont., pleaded guilty on July

16, admitting that he sought to have his agent, David Frost, murdered.

The plan unravelled when the would-be hitman turned out to be a police

informant.

Frost, who was never harmed, has frequently denied he was the target.

As part of a deal with prosecutors, the U.S. government dropped a related

charge against Danton of making a telephone call in connection with

the murder-for-hire plot. Danton could face seven-to-10 years in prison

and a $250,000 US fine at sentencing.

A federal jury on Sept. 20 acquitted co-defendant Katie Wolfmeyer of

charges that she helped Danton in the plot. Danton met the teenaged

Wolfmeyer at an area mall where the Blues practice.

Danton's lawyer, Robert Haar, said Tuesday "we were ready to go

forward (with sentencing) Friday. We would like to get it resolved as

soon as possible."

With files from CP Online

From CBC.ca