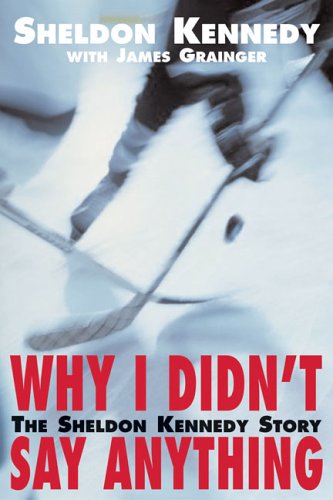

2006 has become the year of freedom for Sheldon. On April 16, 2006, his autobiography, "Why I Didn't Say Anything" was released in Canada throgh Insomniac Press. The release in the USA for this book was slated for October 1, 2006.

As of this writing, we are very happy to report that Sheldon is currently studying for his drug counselling degree and spending time with his ten-year-old daughter, Ryan, whom he dedicated the book to.

Way to go, Sheldon... congatulations...

you deserve it!

Order the book:

Insomniac Press _/\_ Amazon Canada _/\_ Amazon USA

![]()

Below are the archives for 2005 and 2006.

2005

Out

Of The Shadows

(Thanks Rosalyn!)

2006

Healing

Continues For Kennedy's Mom

(Thanks Rosalyn!)

Kennedy Emerges From The Darkness

Molested NHLer Finally Finds Peace

Former NHLer Kennedy On The Road To Recovery

Kennedy Admits To Thinking About Having Abusive Coach Killed

The Perfect Place For A Coach In Exile

![]()

Sheldon Kennedy finds new life

helping Olympic athletes

By ERIC FRANCIS -- Calgary Sun

Fresh off a six-month stint in a California rehab centre, Sheldon Kennedy is ready to make a comeback. Not as a hockey player.

As a person.

Still haunted by demons born out of a sexually abusive relationship with former junior coach Graham James, the ex-Flames winger had disappeared from public view the last five years battling drug and alcohol problems that spiraled out of control and cost him his marriage.

"I went down and dealt with issues," said Kennedy, 36, in his first interview in well over a year.

"It was the first time that I actually made the choice to go down to go there on my own and actually want to do it. All the other times, everybody else told me I had to.

"It took me a long time to get my act together but for the first time ever I'm actually a work in recovery. I go to meetings on a daily basis and I work the steps.

"I realize that if I don't have that I don't have my daughter and I don't have anything."

A brilliant junior hockey player who turned to alcohol as a teen to numb the pain of James' horrific dominance in Swift Current, Kennedy is now hoping to achieve a sense of normalcy he's never had.

"I'm just trying to live my life because, before, I never lived -- I never felt anything. I was numb," said Kennedy, who was named Canada's top newsmaker in 1997, one year after telling police about James' rampant sexual deviance, which led to a three-and-a-half-year jail sentence for the former Hitmen coach.

"It's been nine months since I had a drink or did drugs," Kennedy said. "I'm healthy and ready and now I want to give back a little."

And he wants to do that through a series of athlete-driven initiatives he's working on, including a private-sector organization called See You in Torino that raises money for Olympians so they can focus solely on sports. It was at a fundraiser for the group Wednesday he made his first public appearance in years.

"This is the first time I felt comfortable enough to come out in public -- I was nervous today," said Kennedy, who represented Canada at the 1988 and 1989 World Juniors but had his eight-year NHL career marred by personal issues.

"I want to help these athletes because I know what it feels like when your passion is stolen.

"I think it's important to have a free mind. They say competition is 75% mental and if we can eliminate the mental struggles these athletes have, they're going to have a hell of a lot better chance at doing better.

"I know what it's like to perform and play with a lot on your mind and it's not fun. Maybe a part of me wants to create that freedom for them.

"I was talented enough to make it to the NHL despite all the circumstances. The way I was living, I was wrecking it every chance I had. If I hadn't had that passion stolen, I think I could have done a hell of a lot better."

Well-known for championing sexual abuse awareness programs like Hockey Canada's 'Speak Out,' Kennedy skated across Canada in 1998 on inline skates to raise $1.5 million for what he hoped would help build a ranch for abused children. The ranch never came to pass and the money was given to the Red Cross. But his dream of helping children lives on.

"I was really scared for a long time to get involved in anything because I knew I'd screw it up and I didn't want to," said Kennedy, who lives with his girlfriend on a farm south of the city where he boards horses.

"Now I feel strong enough and I'm ready to ease into things. I feel like I can be accountable now. I feel good today for the first time ever."

He pauses.

"Hopefully tomorrow will be good, too."

INSIDE TODAY'S PAPER -

News & Views in Record time

Record, The (Kitchner, Ontario, Canada)

October 8, 2005

MONDAY IN HISTORY

Seven years ago today, in 1998, former hockey player Sheldon Kennedy completed his 8,150-kilometre cross-country skate to raise awareness and money to fight sexual abuse. He raised $2.8 million for Anaphe Ranch, a treatment facility in B.C., for victims of child abuse. Kennedy had turned the hockey world upside down the previous year by telling how Graham James, his junior hockey coach, had sexually abused him.

Also on this date in:

1885 -- The Victoria Opera House opened with a local production of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Pirates of Penzance.

1920 -- Pianist Thelonious Monk, one of the most influential figures in modern jazz, was born in New York.

2003 -- Iranian lawyer and human rights advocate Shirin Ebadi won the Nobel Peace Prize for her focus on human rights, especially on the struggle for the rights of women and children.

Copyright © 2005, The Record. All

rights reserved.

Art honours abuse survivors -

Many handprints on giant angels Artist appealing for assistance

Toronto Star, The (Ontario, Canada)

May 3, 2005

Author: Peter Edwards; Toronto Star

Creators of a massive monument to child abuse victims say they need a helping hand to keep their dream alive.

They have already received literally hundreds of helping hands, from artists, schoolchildren and countless others, for the giant piece, which depicts two soaring angel-like figures covered with handprints of abuse victims.

Now, they need $450,000 - including $105,000 over the next month - to complete the monument.

Among the handprints on the giant artwork is that of Martin Kruze, who committed suicide after the sentencing hearing for Gordon Stuckless, who abused Kruze while Stuckless worked at Maple Leaf Gardens as an usher.

Kruze killed himself by jumping from the Bloor Viaduct in 1997, just days after Stuckless was sentenced to two years less a day for sexually abusing 24 boys.

"This cannot be shelved," Kruze's father, Imants Kruze, said yesterday, gesturing toward the towering artwork in a studio on Birch Ave.

The artwork has been housed in donated space at the studio. However, that space is only available for another month, leaving artist Michael Irving little time to find it a new home.

Irving, himself a survivor of childhood abuse, would eventually like to see the artwork bronzed and placed at the Air Canada Centre.

He smiles broadly when he talks of the effect it had on Sheldon Kennedy, a former Boston Bruin hockey player and child abuse survivor.

In a visit to the studio, Kennedy gestured grandly at the artwork and said "Let's see them try to sweep this under the carpet."

The artwork includes an archway big enough for three people to walk under and will weigh some 4,500 kilograms.

Irving and Martin Kruze talked often about the project in the months before Kruze took his life.

Kruze's family accompanied Irving to the funeral home where his body lay, and they fashioned a "death mask" of one of Kruze's hands.

"Martin's blessing is here," Imants Kruze said yesterday. "He met Michael before he took his life. He was very impressed with the project, the genius that Michael has put into it."

Irving said that abuse victims and pedophiles alike have been moved to tears seeing the unfinished work in the studio. He said the work stimulates healthy discussion.

"One has the feeling that they're not alone," he said. "It's here. It's tangible. It has meaning. This is what we need."

Caption:

Simon Hayter toronto star Michael Irving, creator of a monument honouring

child abuse victims, says $450,000 is needed to move the work out of

its donated studio space and to complete it.

Copyright © 2005, Toronto Star Newspapers Limited. All rights reserved.

Healing continues for Sheldon Kennedy's mom

By PAUL FRIESEN -- Winnipeg Sun

The first time I spoke to Shirley Kennedy, it was either my first or second day at the Winnipeg Sun. The first week of January, 1997.

That week, junior hockey coach Graham James had pleaded guilty to sexually abusing her son, Sheldon, over a period of several years.

I could hear the pain in Shirley Kennedy's voice over the phone that day.

How could she not have seen what was happening? You can only imagine how many times she's asked herself that question.

Nine years later, her son appears to have finally turned his life around. He's stopped abusing drugs and alcohol. He's become a dependable father. He's even written a book about his ordeal.

Judging by the sound of her voice, mom is doing better, too.

"It will always bother me," Shirley Kennedy told me from her home in Virden. "But ... Sheldon made a point of saying, 'It wasn't your fault, mom.' I also learned an awful lot about how predators work. That helped me understand that I was a victim. Our whole family were victims of this predator. Because every predator works the same way."

That might be the best thing that comes out of Kennedy's book: a better understanding of how abusers work, and how to watch out for them.

"Most people ... don't really understand the effect something like this has on a person," Shirley said. "And they also don't believe it can happen to them or to their children or to a person they love. It can happen."

As for Kennedy, he's hitting the books, taking an addictions diploma course through McMaster University.

It sounds harder than any NHL training camp he ever had to go through.

"I'll tell you, I'm blowin' the old dust off the brain," Kennedy said. "Finally using the brain cells, instead of throwin' them out the window."

After another year, he hopes to land a job with the NHL Players Association's substance abuse program.

"I feel relieved at what he is doing with his life right now," Shirley said. "I feel very grateful, to be honest, because we could have lost him many, many times before. I just feel grateful we have him in our life."

Tue, April 4, 2006

Kennedy comes clean

Former NHLer reveals all about his troubled life in new book

By ERIC FRANCIS, CALGARY SUN

SHELDON KENNEDY ... Amazed he's still alive. (SUN file)

Holed up in the furnace room of his ranch house south of Calgary, Sheldon Kennedy sat with a loaded shotgun in his hands and a bag of cocaine by his side.

In a the midst of a week-long drug and alcohol binge that saw him leave the house only to pick up more cocaine, the former NHL player's paranoia had him convinced there were strangers in the house.

Unable to sleep for two decades without nightmares of the sexual abuse he endured from junior hockey coach Graham James, Kennedy's inability to close his eyes for four days now stemmed from a different source of shame and isolation he tried hiding from the world -- his substance abuse. And although he'd been lost in countless drug- and alcohol-induced hazes before, this time he was sure he was about to die.

"I looked in the mirror and I was 135 pounds -- I had hit rock bottom," said Kennedy, recalling Dec. 7, 2004.

"I picked the phone up and called a friend in L.A. for help. She got hold of the NHLPA's substance-abuse program and I was done. I surrendered.

I haven't touched anything for 16 months."

It's been nine-and-a-half years since Kennedy took the first step towards relieving himself of the terrible burden that comes with suffering silently through years of sexual abuse.

However, despite a cross-Canada inline skate, a brief NHL comeback, a failed marriage and fatherhood, Kennedy's road to recovery had to go through a California rehab centre for six months before he could really get on with his life.

"With all the stuff I did to my body with the drugs and alcohol, it's amazing I'm still alive," said the former Flame (1994-96), sitting in a Calgary cafe for an exclusive Sun interview.

"Before, I had a lot to hide and booze made me feel comfortable around people. Alcohol controlled my life. I'm not sure if I was born with it or Graham made me do it but alcohol and pot made me sane and eventually it got to the point it almost killed me."

Insisting for the very first time he has control of his life, Kennedy spent the last year of sobriety penning his thoughts for a soon- to-be-released book, Why I Didn't Say Anything. Unlike during his inline skate to raise money and awareness for abuse victims, Kennedy feels that now he's helped himself, he can help others deal with emotions associated with abuse.

"Throughout the skate, I felt like a guy with a brown bag sitting on the street corner and then I'd have to go into a phone booth and throw the Superman cape on," said Kennedy, 36, who tarnished the skate by crashing a Hummer in Edmonton after drinking eight beers.

"That double life was eating me up because, yes, I was carrying the message of abuse but I still had a lot of shame and guilt from the drinking. I was getting 10 disclosures a day but I hadn't dealt with my own."

The book documents the abuse which started when Kennedy was 14 and takes the reader through the levels James went to cover his tracks:

How James had the audacity to abuse Kennedy in his parents' basement while they slept; how he refused to allow players therapy after a bus crash killed four Swift Current Broncos players; how he traded any player who got close to Kennedy; and how he painted Kennedy as a troublemaker and liar so potential abuse claims would be discounted.

Kennedy writes about how James paid players to have sex with girls while he watched from the closet; how players around the league taunted Kennedy for being 'Graham's little wife;' and how many people knew, or ought to have known, about the abuse that police estimate affected 75 to 150 of James' players.

Kennedy said fears NHLers knew of the abuse led him to try cocaine in 1990 as a Detroit Red Wing. Moving in with teammate and convicted drug smuggler Bob Probert only escalated the substance abuse.

Now a counselor with Calgary's ARC drug rehab centre, Kennedy is taking online classes with hopes of working with the NHLPA's substance abuse program that saved his life.

A life no longer burdened with secrets.

Kennedy emerges from the darkness

Abuse victim puts fear and guilt behind him

ALLAN MAKI

CALGARY — You look into his eyes and see something that wasn't there two years ago when he sipped his morning coffee and admitted he couldn't sleep at night because of the sounds he kept hearing -- the creaking floor and the clicking of a hot-air vent, as if someone was opening a door.

They were sounds that unlocked the memories of his tormentor crawling on all fours toward him, a predator in the dark. But on this day at a neighbourhood Tim Hortons, there is something in the eyes of Sheldon Kennedy that shines through the hurt. There is clarity; there is hopefulness. And for the past 16 months, there has been sobriety.

This is all new for Kennedy. For too long, he stared at people doing everyday jobs and wished he was one of them. Instead, he was the National Hockey League player who confronted Graham James and sent the former junior coach to jail for sexual abuse. For that, Kennedy was chosen as the Canadian Press newsmaker of the year. He appeared on Oprah, chatted with Rosie O'Donnell and even had a television movie made of his unthinkable ordeal.

Everyone considered Kennedy a hero, but all he wanted was to be normal, to feel normal. These days, he's happy to say he's finally getting a taste of that.

"I feel like I'm 21 and just starting out," he said yesterday while looking the part -- his hair spiked and styled, and his grey sweater and black sports coat fashionably matched. "I never thought I could live without fear and guilt. Now, I'm up at 5:30 a.m., dressed and ready to go, and I plan my days. I never planned anything before because I didn't care."

Kennedy hasn't been in the news for the past two years and that's been all right by him. He needed the time to clear his head and to get off the drugs and alcohol that were the easiest way to cloud his mind.

He also agreed to write a tell-all book that will be released this month. The book's title is Why I Didn't Say Anything: The Sheldon Kennedy Story and it is a heartbreaking account of how Kennedy felt no one would believe him had he gone to the police at the age of 14 or 15 and said, "My hockey coach is sexually assaulting me."

Later, after he had left the Swift Current Broncos of the Western Hockey League, Kennedy tried to forget rather than react to all that had happened to him. He played in the NHL with the Detroit Red Wings and the Calgary Flames. He'd go hard on and off the ice. His lifestyle, he said, "was brutal. I ask myself now, 'How did I play in the NHL?' I never rode a bike or lifted a weight. How did I hang in there?' "

Eventually, the drinking and denying proved too much. Kennedy's wife, Jana, persuaded him to go to the police and charge James. The Canadian hockey establishment was stunned to learn what James had been doing to Kennedy and one other player. The end result was a jail sentence for the coach, but no inner peace for the victims.

To keep his mind occupied, Kennedy skated across the country on in-line skates to raise money and awareness for sexual abuse. He had breakfast with the prime minister at the time, Jean Chrétien. People applauded Kennedy's work and figured everything was all right, but it wasn't. The depression returned and led to alcohol abuse, which only intensified the fear and guilt.

Then it all unravelled. Kennedy and his wife divorced. There was a rehabilitation stint at a California treatment centre. There was news that James was out of jail and coaching a club hockey team in Spain. When he heard that, Kennedy couldn't sleep because "Graham would crawl around at night and I thought I could hear him in the room."

Sixteen months ago, realizing he was hell-bent for oblivion, Kennedy joined Alcoholics Anonymous. Writing about his experiences wasn't so much therapy as it was symbolic -- one saga ends, a life begins. It is a life Kennedy is learning to appreciate.

"I couldn't understand how people got up to go to work every day or how they'd sit back and read a book," Kennedy said. "I couldn't sit for two minutes and be comfortable in my skin. Writing my book, I had to look at my part in all this, how I acted out, all the drinking. I had to go to the biggest, deepest, nastiest things, then clean house. . . . I'm learning to live a totally different way."

For the man who once suffered in silence, the beauty of life is now its simplicity. He feeds his horses on his 60-acre farm south of Calgary. He answers e-mail, arranges his speaking engagements and, best of all, dotes on his 10-year-old daughter, Ryan, who wants to play hockey in the fall.

"I'm fine with that," he said with a smile. "I'm at a place where I can take care of myself. Get this: I believe I can actually do stuff now."

Molested NHLer finally finds peace

Sat, April 8, 2006

Sheldon Kennedy tells all in autobiography

By JUDY MONCHUK

CALGARY (CP) - Sheldon Kennedy's darkest hour came huddled in his furnace

room with a shotgun and a bag of cocaine, sleep deprived and paranoid.

The former NHLer who shattered Canadians' wholesome view of hockey by revealing his junior hockey coach Graham James molested him for years was certain the sexual predator who haunted his nightmares was still able to harm him more than 20 years after the abuse.

"It made me realize I was either going to die or I needed to deal with the demons inside me and answer the question of why I didn't stand up for myself," said Kennedy, now 36.

That low point 18 months ago is detailed in Kennedy's autobiography Why I Didn't Say Anything, a book he describes as a red flag to parents.

Kennedy was a 14-year-old farm kid when the molestation began, the first night he stayed with James on a trip to Winnipeg for a hockey tournament. After being rebuffed by the teen, James pulled out a shotgun and began talking about how much he enjoyed killing ducks.

The next advance met no resistance.

The book details how the respected coach isolated Kennedy from his family and teammates. It recounts the inner turmoil faced by a child taught to respect authority figures, who fantasized about playing in the National Hockey League.

James told anyone who would listen that Kennedy was a troubled kid who needed help, a prophetic description as the youth turned to booze, pot and eventually cocaine to help cope with his guilt and shame.

Heralded as a hero for going public in 1996 about the abuse, Kennedy embarked on an in-line skate across Canada to raise awareness of the issue. But he was unprepared for the emotional toll that came when a flood of victims as old as 65 confided in him that they, too, had buried tales of abuse.

"When I was skating across Canada, I was getting 10 to 15 disclosures a day," Kennedy said softly. "I didn't know what to do with it. The skating was the easy part. I didn't know how to deal with the disclosures and handle them and let them go."

That burden was ultimately too much to bear. Kennedy pushed aside his wife and retreated back into the binges which he had used for years to help numb the pain, through stints with the Detroit Red Wings, Calgary Flames and Boston Bruins.

"When I went to bed I was (afraid) to go to sleep because I feared somebody would take advantage of me while I was sleeping," he said. "When I woke up I was so scared of the day. I was so scared of life and just living. It was just brutal. Now I wake up and I enjoy life."

Kennedy has finally made peace with his demons. He's been a member of Alcoholics Anonymous for over a year and finds it has given him the structure to cope.

"Drugs and alcohol (allowed) me to escape and not deal with the daily things," he said. " Now I feel I have the tools to handle those types of things."

Despite his pronouncements that life has turned around, an aura of frailty surrounds Kennedy. Dressed all in black, he looks smaller than one might expect and the toll of his life experiences are evident in the lines around his eyes.

James is under a lifetime coaching ban in Canada after serving almost three years in prison for molesting Kennedy and another member of the Swift Current Broncos of the Western Hockey League. But he's been coaching in Europe.

And while Canada's minor hockey volunteers must now go through criminal record checks, references and interviews, Kennedy doesn't believe that eliminates the possibility of another predator lurking behind another bench.

"We'd be very naive to think that with 650,000 kids in minor hockey and 25,000 coaches that we're exempt from another predator who wants to prey on kids," he said. "I still think there's a fear of people saying anything - especially in small towns. Nobody wants to stand up and rock the boat. There are things in place, whether it's enough, I'm not sure."

Parents must realize that they can't trust everyone.

"I don't think we can just rely on systems to protect our kids," said Kennedy, the father of a 10-year-old girl. "We drop the kids off at the rink or soccer and say 'listen to your coach.' We as parents need to pay a lot more attention."

Kennedy is working towards an addictions counselling diploma and wants to eventually work with the NHLPA's substance abuse program. He spent the last few months at the Alberta Adolescent Recovery Centre, helping teens with those own addictions.

"A big part of recovery is to give back," he said. "I couldn't give back properly until I could take care of myself. I feel like I'm there now. I can relate to a lot of the kids and people who are in those situations. I know what one has to do to get the type of peace that's needed to live."

Kennedy has heard that one of James's other victims now has a young son involved in hockey, but that the father can't bring himself to go to the rink.

"That's sad," said Kennedy. "I pray that they can find a type of peace, but they can't do it on their own. It's haunting every day living with that."

There are positives on the horizon. He has joint custody of his 10-year-old daughter Ryan and he's on good terms with his ex-wife, Jana. He wants simple pleasures that many people take for granted.

"I'm not expecting much," he says with a smile. "I just want an inner peace where I can enjoy life with Ryan, with my family. I'm just learning to do that. It's like I'm starting to venture into life and my motto is keep it simple."

Former NHLer Kennedy on road to recovery

Sexual-abuse victim puts life back together as he studies for addiction-counselling

degree

KERRY WILLIAMSON

CanWest News Service

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

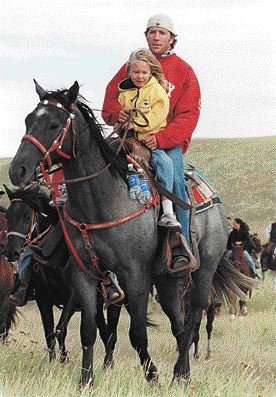

(PHOTO CREDIT: IAN MARTENS, CP

Former NHLer Sheldon Kennedy and his daughter, Ryan, take part in the

Sheldon Kennedy Trail Ride to increase awareness of a Red Cross child-abuse-prevention

program near Stand Off, Alta., in 2001.)

Sheldon Kennedy could no longer step inside a hockey rink, or even watch

a game on television.

The dressing rooms were filled with too many ghosts; the pain still too deep.

He hadn't had fun on the ice since the days before he met Graham James, the coach who sexually abused him at least 300 times, destroying his life and stealing away his passion for a game he once loved.

But after a year without a drink, and a rebirth of sorts, Kennedy decided it was time. A few months ago, after another stint in rehab, he stepped on to the ice at the Calgary Saddledome ice again.

And with that, Kennedy knew he was back where he belonged, a place he hadn't been to since he was a kid.

"That freedom out on the ice," said the 36-year-old, who rocked the hockey world a decade ago when he charged James with sexual abuse. "I hadn't had that throughout my entire career.

"And it was nice out there. I was nervous, being in the rink and being in that atmosphere. But I'm finally enjoying it. It's just nice to feel comfortable in the rink again. That was my life, I loved it, but it was stolen from me for a long time."

It's a different Kennedy that orders a strong, black coffee at a coffee shop near his home south of Calgary, a place where he studies for his addiction-counselling degree, something he hopes will soon return him to the National Hockey League.

He is no longer the life of the party, the guy who drank teammates under the table, rode a Harley-Davidson motorcycle while with the Detroit Red Wings, and hid his demons from everyone close to him. He drives a truck, smokes the odd cigarette and wears a rubber bracelet that reads Courage to Change.

He has emerged from the shadows of abuse and drug and alcohol addiction, described in detail in his new book Why I Didn't Say Anything.

Kennedy has become a regular at Calgary Flames alumni games and can now talk about the horror that earned James a 31/2-year stint in prison instead of burying it with beers, pot and cocaine.

It has been 10 years since Kennedy called police in Calgary to tell them what James did to him, 22 years since James first abused him at the coach's Winnipeg home where he was billeted. He still remembers that first night, when he awoke to find James touching his feet then later brandishing a shotgun near the cot where he slept.

He still finds it difficult to sleep, when the most innocent of sounds can send his thoughts back to those nights at James's apartment. But three months at a California rehab centre, and four to five Alcoholics Anonymous meetings a week have Kennedy dealing with his past, and finally looking forward to a future.

"The fears of not feeling safe, they will always be there," he said. "He (James) used to crawl around at night, when you went to bed, so there's that fear of somebody getting you when you fall asleep.

"I can get through it now, but it's there. I have to make a conscious decision to make sure I get myself through that."

Only 18 months ago, that seemed unlikely. Kennedy's darkest hour came when he locked himself in his furnace room, shotgun by his side, high on cocaine, scared people were coming to get him. When he finally emerged, he knew he had a life-or-death decision.

He called a friend in the NHL Players' Association's drug abuse program, and checked into rehab.

"Eventually, I had to surrender. Being a hockey player and growing up on the farm, I was a fighter, I didn't like to surrender," he said. "It felt like it was another loss to Graham. But I just couldn't hold it in anymore. I was done."

His recovery is still in its early stages, but he is determined to stay clean. He avoids bars, prefers to stay home and read books or spend time with his horses. He has a close circle of friends, including his ex-wife Jana.

He even hopes to return to the NHL, working with the PA's drug abuse program. Kennedy no longer dwells on the past, on what James did to him, on his hockey career, on his charity skate across Canada or on the accolades that followed.

"I'm just starting to live," he said. "I think that my story highlighted the sexual abuse stuff long enough for people to make changes, and for that, it was totally worth it. But I don't feel that responsibility now. I'm different now. What's important to me is that I found a way out."

He rarely thinks of James, only the affects of what James did to him. He has heard his abuser is back in Canada, living in Montreal, after a coaching stint in Europe that saw him take charge of the Spanish national team.

"I just think that he is hurting," Kennedy said of James. "He hasn't dealt with anything, and I know that when I wasn't honest about my alcohol abuse, I never got better.

For now, it's about recovery. Now that he's got that love back, he plans to keep on skating, with his alumni buddies at the 'Dome, and with his daughter Ryan.

Now 10 years old, she is starting to play hockey and has a passion for the game not unlike her father 25 years ago.

And in a sign that Kennedy has, indeed, come full circle, rather than shield his daughter from the game that almost killed him, he is contemplating coaching her team.

"I know now I will be all

right. If I can't hold it together now, then it's my fault."

© The Gazette (Montreal) 2006

Sheldon's Story

'Why I Didn't Say Anything' - The Sheldon Kennedy Story about sadness,

hope, abuse and addiction all rolled into one

By DEREK VAN DIEST, EDMONTON SUN

Sheldon Kennedy hit rock bottom 16 months ago.

During a drug binge that kept him awake for seven days, the former NHLer took a shotgun and a bag of cocaine to the furnace room in his ranch house and waited for his enemies.

After years of enduring sexual abuse from his former junior hockey coach Graham James, and then developing drug and alcohol problems trying to deal with it, it had come down to this for Kennedy. He was not going down without a fight.

"I had to get there," Kennedy said. "I had to get to a place where I had one decision to make. The decision was to make a phone call or die pretty much."

Kennedy, 36, made the call to a friend in Los Angeles.

Together they drove down from Calgary to a treatment centre in California.

Kennedy's now sober.

He's written a book, Why I Didn't Say Anything - The Sheldon Kennedy Story, due out next week. He's trying to get on with his life. Like many recovering addicts, he's taking it one day at a time.

"I'd been asked to write a book a few different times in the last five years and I felt that I just wasn't done the last chapter," Kennedy said. "I felt I needed to see a way out, to maybe give people hope and an ending of the story.

CHRONICLES HIS LIFE

"I think I got to that point. I've seen a little bit of freedom, a little bit of peace, and felt it was time to write the last chapter and hopefully put an end to this chapter of my life."

In the book, Kennedy chronicles his childhood in Thompson, Manitoba, his relationship with his parents, and his first acquaintance with James - a man who would change his life forever.

Kennedy describes how the abuse began the first night he stayed with James as a 14-year-old at a tournament in Winnipeg.

It continued through junior hockey in Swift Current, Sask., where Kennedy also had to deal with the loss of four teammates following a bus crash on Dec. 30, 1986.

He talks about the lengths James went to in order to keep the abuse secret. How he labelled Kennedy a troubled teen so it would appear the junior coach was reaching out and going out of his way to help him.

How twice a week Kennedy would have to go to James' home for 'tutoring sessions' where the abuse took place.

How there was talk in the community and around the league something was going on, but no one did anything about it.

"It wasn't really that tough to write about," Kennedy said. "It was stuff that I had to look at to get the freedom I was looking for in recovery. I had to go to those places. For me, it was just nice to be able to put it down on paper.

'JUST AN HONEST STORY'

"I felt I could write it and really feel some freedom with it. Feel like 'Here it is.' It's just an honest story - it was quite easy to put down. There wasn't this fear of writing something down and trying to protect a secret. For a long time, I was living a double life. I think it was just really nice to be able to put it down on paper the way it was with a way out, to give people a little hope without worrying about trying to protect something."

The book also chronicles Kennedy's struggles with drugs and alcohol during his NHL years. He talks about his relationships with his ex-wife Jana and how she supported him when the decision was made to press charges against James.

It takes readers through his inline skate across the country, raising the awareness of sexual abuse.

And it concludes with Kennedy's downward spiral into a world of drug-induced paranoia and the struggle to conquer his demons.

"I'm really happy with the book," he said. "It's not a pity book. It's not a preachy book. It's a book of sadness and hope put together. I think that it's kept simple. I think the issue of addiction and abuse all rolled into one can be very complicated for people.

"With me, I think the title pretty much says it all, because that's the biggest question I used to ask myself and that's the biggest question I used to get asked.

"I think its explained fairly well in there how difficult it is. It's not a hockey book; it's a red flag book for parents. I think that's what we wanted to accomplish was to keep it simple, but to keep it hopeful as well."

For the first time in a long time, there is hope in Kennedy's life.

He's going to school, working on an addictions counselling diploma and hopes to work with the NHL substance abuse program. He's also close to his family and has a great relationship with his 10-year-old daughter, Ryan.

"I'm doing this one day at a time, staying close to the meetings and other people in recovery," he said.

"The most important person to me is Ryan and the most important thing is recovery because if I don't have it, I don't have anything."

Fears finally fading

Kennedy book tells tale of despair after sex abuse

By PAUL FRIESEN

And we thought the Sheldon Kennedy story had a happy ending, all those

years back. It sure seemed that way at the time.

Sexually abused by his junior hockey coach, Graham James, starting when he was 14, Kennedy put James behind bars in 1997.

Then he in-line skated across Canada, raising all kinds of money and awareness for abuse victims along the way.

He even tried a hockey comeback with the Manitoba Moose in '98. It didn't work out, but surely Kennedy had turned his troubled life around.

At least, that's what we wanted to believe.

The truth is, Kennedy's life was spiraling downward, fueled by drug and alcohol abuse, until it finally hit rock-bottom on Dec. 7, 2004.

Living in a Calgary-area ranch house that he'd gutted, with no furniture or food, the Elkhorn, Man., native went on a week-long binge, getting no sleep and ingesting nothing but cocaine and tap water for seven days.

Down to 135 pounds, Kennedy barely resembled the man who'd spent eight years in the NHL.

Paranoid someone was in his house and out to get him, Kennedy holed himself up in his furnace room, loaded shotgun in one hand, bag of cocaine in the other.

"At that point I really felt like I didn't have anything anymore," Kennedy told the Sun in an interview yesterday. "And I had a choice to make: make a phone call to get help, or keep this going until I was dead."

The startling admission is one of several in Kennedy's book, Why I Didn't Say Anything - The Sheldon Kennedy Story, due in stores next week.

Written during Kennedy's first year of sobriety since he was a teen, the book is a riveting account of the abuse he suffered playing junior hockey in Moose Jaw, Winnipeg and Swift Current, and the resulting shame, guilt and substance abuse that plagued him through his NHL career, and beyond.

At times, it's the kind of story you want to put down, but can't.

It describes how James wormed his way into every facet of Kennedy's life, conning everybody into believing he had his star player's best interests at heart.

James was so convincing, Kennedy's parents even invited him to stay at their farm in Elkhorn, where James abused their 15-year-old son in the basement -- while they slept upstairs.

"Those are the things that chewed me up," Kennedy said. "Like, why the hell would I let that happen?"

The account of the first time James abused Kennedy, in his pitch-black St. James apartment, is equally chilling. When Kennedy spurned James's advances, the coach pulled a shotgun out of his closet to make sure the kid knew he meant business.

Some 22 years later, Kennedy's night-time fears are finally subsiding. He's able to turn off the light and go to bed, without the horrifying image of James closing in on him every time.

The book also deals with the conflict Kennedy went through during and after his in-line skate. As the face of abuse victims, he was a public hero. Behind the scenes, though, he was still a drunk.

Two years ago, he finally began confronting all his demons, "stuff I thought I'd take to my grave, and (was) eating me up."

The abuse. The guilt and shame it created. Why he didn't do anything sooner. The loss of his NHL career, and the depressing realization he'd hated every minute of it.

And, yes, his own part in ruining his life with alcohol and drugs.

Until he'd confronted that demon, and wrestled it into submission, he wasn't ready to put his story down on paper.

"I just felt like I hadn't finished the last chapter," Kennedy, 36, said. "I wanted to get to a place where I found a way out, found a little bit of freedom."

A happy ending? It's too soon to say.

But it's a much better read than it used to be.

---

Despite outing Graham James years earlier, Kennedy didn't hit rock-bottom until just over two years ago -- as he explains in his book:

My house was torn apart and half rebuilt -- no furniture, no furnace in the winter, no food in the fridge. It was like living in a crack house. I was utterly helpless because of my addiction. I didn't leave the house unless it was to get more coke. I would buy an ounce of coke at a time and that was what I lived off: coke and the water from my tap ...

I hadn't had the guts to kill myself like I'd wanted to for the last twenty years but I'd finally found a way of living and a drug that would do it for me. I had nobody. I had pushed away every person who ever tried to help me ...

I completely isolated myself in that giant gutted house. I felt like I had gone there to die. I then went on a coke binge that kept me up for seven days straight. By the third day, I was convinced that there were people hiding inside the house. They were after me. I had to find them. I did patrols all day and night through the house carrying my shotgun ...

Finally, I took my gun and my bag of coke and holed myself up in my furnace room, the only safe room in the house, or so I believed ... I had finally hit rock bottom. The only thing left to do was die.

Kennedy admits to thinking about

having abusive coach killed

By PAUL FRIESEN -- Winnipeg Sun

Sheldon Kennedy says he could easily have been another Mike Danton.

Danton, the troubled former member of the St. Louis Blues, is in a U.S. prison, serving a seven-year sentence for attempting to hire a hit-man to kill his former coach and agent, David Frost.

Kennedy says the Danton-Frost story, particularly the strange hold Frost has had over Danton since the player was in his teens, reminds him of his nightmarish experience with Graham James.

And, yes, the thought of having James killed crossed Kennedy's mind, more than once.

"Oh yeah, I was definitely there," Kennedy said. "I could have been (Danton). Mike Danton acted on thoughts. I went inward. It's just sad to me that he's in jail for seven years."

Kennedy says it was "really eerie" watching a recent CBC documentary on the Danton case, and hearing the bluster and bravado coming from Frost.

"It just reminded me of that power that Graham had," he said. "It's almost like a brainwashing."

Kennedy has never spoken to Danton about Frost. But he has talked to players he believes were also abused by James.

"I've talked to a few guys," Kennedy said. "It's up to them to deal with it in their own time, their own ways. But it's pretty sad. A lot of these guys loved the game, and now they don't even play rec hockey because they don't even enjoy going to the rink."

James pleaded guilty in 1997 to more than 300 incidents of abuse against Kennedy and another player who chose to remain anonymous. He was handed a 3 1/2-year prison sentence.

After his release, James landed a job in the Spanish national program.

Kennedy says he'll always respect the other players' privacy, but ...

"I was frustrated when Graham was coaching in Spain that somebody didn't charge him and get him out of there, put him back behind bars," Kennedy said.

The last Kennedy heard, his abuser was living in Montreal, although James is banned for life from coaching in Canada.

---

Kennedy describes how James chose his victims:

Graham was very good at picking out his victims. He would feel them out first, looking for weaknesses and insecurities before he made a sexual move on them ... looking for boys who didn't have a very solid home, boys whose fathers were angry and had drinking problems. Kids with single moms were on the top of his list of potential victims.

He wanted to find boys who needed a father figure in their lives, boys who were confused and unsure of their masculinity and needed a man they could trust and confide in. When he found someone in that situation, he swept into their lives like Superman. But what the parents didn't know was that Superman was planning to take their sons into a very dark dungeon and that their sons might never make it out of that dungeon.

---

Kennedy talks about the first time James abused him. He was 14 at the time:

I was almost asleep when I heard Graham crawling around near the end of the cot. He started rubbing my feet, telling me that a foot rub was the best thing for the body after a hard day. I felt very uncomfortable but let him do it for awhile. Eventually, I couldn't take it anymore and pushed him away ...

I thought that would be the end of it. It was just the beginning. I heard Graham moving around in the dark on the other side of the room ... he opened a closet door and seemed to pick up a heavy object. There was more movement as he made his way back to his bed, and then he flicked on the lights.

When I opened my eyes in the sudden brightness, I saw Graham sitting in bed cradling a shotgun. He was smiling, but it wasn't a smile I'd ever seen before. He looked crazed. His eyes were almost glowing in his head. He was out of his head, but I'd never seen him looking so sure of himself and what he was doing ...

He knew the effect the gun would have on me. I was alone in a strange place with a strange man who held the keys to the world that I had wanted to be part of since I was a little kid. He was a man who'd I'd been told to look up to and obey. He knew all of this, and he knew he could use his authority and my fear and ignorance to get me to do something that I didn't understand and didn't want to be a part of ...

When I resisted, he went away to get his next weapon, and when he turned on the light, he showed me what would happen if I didn't co-operate.

---

James continued to prey upon Kennedy, even in the unlikeliest of places:

Later, after he became my coach, Graham even came out to the farm with me on a few occasions. My parents didn't seem to think it was strange that he asked to sleep in the finished basement where I slept in one of the spare beds. In the middle of the night, he could come for me as he had in his Winnipeg apartment. He would abuse me while I lay there pretending that I was knocked out or asleep or somewhere else.

The next day, he sat down to breakfast with my family, acting as if everything was normal. I was in total shock. If Graham could get away with this in my own house, with my parents sleeping upstairs, then there was nothing he couldn't do to me.

The perfect place for a coach in exile

Greg McArthur and Gary Dimmock

The Ottawa Citizen

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Until the Junior A hockey team came to town, there were only two reasons

to visit Deseronto: Walleye fishing and cheap cigarettes from the Mohawk

reserve.

It was Marty Abrams, a onetime Washington Capitals draft pick who grew up near Deseronto, who was the visionary behind the team. The idea caused the town to come alive.

People lined up to get involved with the club. Norm Clark, the town's Scottish police chief, was club president. Chuck Morgan, the owner of the Main Street variety store -- appropriately named "The Store" because it was one of the only ones -- became the team's trainer.

Families volunteered as billets and agreed to house and feed the players for the season.

They called them the Quinte Hawks, hoping to attract fans not only from town, but from the entire stretch of land that borders the north shore of the Bay of Quinte, an inlet off Lake Ontario. The arena's nine-by-nine metre storage room was outfitted with a new shower, a paint job and was suddenly a bonafide locker room. A new wooden grandstand increased the rink's capacity to 600. The ice pad didn't lose all of its small-town charm, though. At the west end of the rink, behind the home team's net, there was metal mesh instead of glass. It looked like a chicken coop and the players named it accordingly -- "The chicken wire."

The town finally had something to be proud of. This wasn't just another fishing derby, when the anglers fly in and leave just as quickly. This was for real, the best thing to happen to Deseronto since Hugo Rathbun -- the New Yorker who opened up a timber mill in 1848 on the Bay of Quinte and watched the town blossom.

The team played in the Metro Junior 'A' League -- two steps away from the NHL and one step from a U.S. college scholarship or major junior team like the Ottawa 67's. The league had teams across southern Ontario and in the U.S. It wasn't sanctioned by the Ontario Hockey Association so the rules were a little looser; in this outlaw league the players could fight twice before they were sent to the dressing room, instead of being tossed after one.

The boys came from across Canada: Toronto and Sudbury and from as far away as Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island.

But there was a problem: The Hawks were crummy.

In their first six regular season games they notched only one win. The fireworks -- the team lit fireworks before their home debut against Syracuse -- had faded. Expectations were high, especially in a town that didn't have a lot to cheer for. Greg Royce, the local high school teacher who coached the Hawks, wasn't producing. He was a nice guy, the players said, but his inspirational speeches, often touching on the ancient wars of history or hockey legends, weren't doing it for them.

The Hawks needed to be pushed.

It was at an October practice in 1996 when Dave Frost and his boys first appeared. "I swear to God for a second everyone on the ice stopped and said 'Holy s--t. Who are these guys?' " says David Maracle, one of two Mohawk boys who made the squad. The six of them stood in the stands, aligned in a row. They wore identical red-and-white Toronto Young Nationals jackets and trendy footwear, Roots Boots. Most of them sported the same haircut, a mullet -- with the sides shaved short and a tuft of hair at the back. "They looked like a gang staring their cold stare, like eagle eyes," says Matt Barnhardt, the other Mohawk forward. "They all kind of looked the same."

Without a word to the players, or even the captain, the Hawks had five new teammates: Larry Barron, Darryl Tiveron, Shawn Cation, Sheldon Keefe and Mike Jefferson -- who would later change his name to Mike Danton and plead guilty to hatching a plot to kill Frost.

Frost, the man with the shiny-tipped cowboy boots and the sandpaper voice was their new assistant coach.

It was the perfect place for a coach in exile.

- - -

There was something different about these Brampton boys.

Three of them -- Barron, 20, Tiveron, 20, and Keefe, 16 -- lived with Frost in a roadside motel room. The younger ones who were still in high school -- Keefe, Cation, 16 and Jefferson, 16 -- didn't say a whole lot and when they did open their mouths it was usually about Frost; Dave didn't want them talking much and Dave thought this was best for their career. In the gym class at Napanee District Secondary School, the Brampton boys refused to do certain games and activities on Frost's orders. Some players found it strange the boys didn't acknowledge the locals, except for a handful of girls. "They wouldn't talk to them. They'd barely talk to the teachers. They did their schoolwork and that was it. Like robots," said Colin Scotland, a winger from Cole Harbour, N.S.

"They didn't make a lot friends in Napanee or Deseronto I would say. They weren't a social bunch. I don't think they know 10 other people in that town," says Morgan Warren, a player from Prince Edward Island.

Some called them a cult. Some called them a clan. The boys would do nearly anything that Frost asked of them. Shortly after Frost showed up, the Hawks had individual meetings with the coaching staff. Jason Flick, one of the goalies, says he was told he was in a slump and his girlfriend was to blame.

He had to get rid of her. The goalie told them he didn't want to end it, so the Brampton boys went to work, he says. A few days later the girl came sobbing to Flick in the high school cafeteria saying she couldn't take it anymore. Some of the Hawks had told her to get out of Flick's life because she was ruining his career. They were giving her dirty looks. It was over, she said. "It wasn't a serious relationship or anything, but who does stuff like that? Whatever he wanted done, got done. That's for sure," Flick says.

Who were these guys? Most players on the Hawks knew nothing about Frost's boys and their past. They had no way of knowing that Frost was running out of leagues where he was welcomed.

Before he rolled into Deseronto, the coach had been reprimanded for his team's violent play and he was forbidden from getting behind the bench in two Toronto area leagues. The Ontario Hockey Association banned him until he responded to allegations he served alcohol to minors during a hazing party. He was also under suspension from the Metro Toronto Hockey League for allegedly forging player release forms. It didn't end there. He had also been rejected by the Metro Junior 'A' Hockey League after he apparently lied to its officials. Before the start of the 1996-97 season, Frost showed up at a Toronto Ramada Inn for a league meeting. He proposed a new franchise and, according to the league's president, told the board he was speaking on behalf of NHL player Andrew Cassels. The president, Bill Markle, was suspicious. "I was kind of surprised he was purporting to be there on behalf of a professional hockey player and had no documentation to verify that," Markle says. They made some calls to confirm that Cassels, who grew up in Brampton with Frost, was involved. The professional player has nothing to do with him, they were told.

Frost had been a coach without a team -- until he got the call from Marty Abrams.

He walked into the job with an impressive resume. He had guided a bunch of 15-year-old kids on the Toronto Young Nationals to a Bantam provincial championship. He also had the five Brampton boys, all of them extremely loyal to their coach. Jefferson, a gritty third-line centre, was the most loyal of all. He hardly spent any time at his billet's house. It was the same routine almost every night, says Elena Phillips, the retired nurse who housed the teenager for the season: He came home from school, ate dinner -- on game nights it was a pasta dish with plain sauce from a can -- grabbed his school books and went to the hotel. He rarely talked but was always home by 10 p.m. curfew.

He was just as rigid and regimented on the ice. He would fight anyone, no matter how big or strong. There was one game when he got into it with a player from Aurora but didn't realize the guy was a lefty. He was pummeled.

He dragged himself into the dressing room at intermission and got an earful. David Maracle remembers Frost telling Jefferson that the teen had embarrassed him. He ordered Jefferson to scrap him again and again he took a beating, the players say. "I think by the third time he fought him it was a draw," Maracle says.

The whole team noticed it: How Frost would order Jefferson to grab him a glass of water and the boy would oblige and how Jefferson would fetch Frost's inhaler at the coach's command. "It was like a dog going to get his master's paper," says Corey Batten, the other goalie.

Jefferson was eager to please this man -- even if it meant giving him a massage.

They were on the bus and, like most road trips, the players stripped down to their underwear. That might sound strange to anyone who hasn't played competitive hockey, but guys often "gear down" when they're coming home from a game. It's a long trip with lots of bodies in a confined area so it's more comfortable if you're in nothing but your boxer shorts.

But it is unusual for your coach to ask for a neck rub.

During one roadtrip, Frost hollered for Jefferson to come up to the front of the bus where the coach was sitting. Frost had taken his shirt off and was bare from his mid-section up. He told the teen his neck was sore. Jefferson sat beside his coach. He worked Frost's neck and shoulders with his fingers for about an hour, while the rest of the players joked and talked at the back, Morgan says.

"I remember thinking what kind of teenage boy comes up in shorts and rubs his coach's back for him?" the trainer said. "Mike never said anything. He just came up, did what he was told and that was it."

It wasn't the only massage, the players say.

One player, Ian Larocque, said there was nothing exploitative about the backrubs. Jefferson had an interest in physiotherapy, he says, and he once gave Larocque a massage when he had an injury. However, Frost told the Citizen he's never heard Jefferson say anything about wanting to be a therapist. By most accounts the only thing Jefferson ever talked about was making the NHL.

- - -

This new assistant coach was no one's assistant. He was speaking up in the locker room. He stalked the bench during games. He leaned with one foot on the boards and cracked his neck from side to side, a trademark twitch the Hawks can still imitate to this day. Greg Royce was still the head coach on paper but that was it. "From the moment Dave Frost got on that bench, Greg Royce became a door opener," says Steve Jefferson, Mike's father who attended nearly every game.

If there was a coming out party for Frost, it was probably the Oct. 27 brawl with the Wexford Raiders, about a week and a half after his boys rolled into town in their Roots Boots.

No one's sure exactly how it started but everyone remembers how it ended: In the corridor of the Wexford arena, two teams in each other's faces, chopping at each other with sticks, swearing and taunting.

Parents were grabbing their kids and dragging them out. LaRocque, the assistant captain, was swinging his stick like a helicopter. The police were called to escort the Hawks from the rink. And where was Frost? In the middle of it all holding a fire extinguisher above his head. It looked like he was ready to chuck it into a crowd of Wexford players and fans. "It would have killed someone," says Barnhardt, one of the players who tried to stop him.

"That was the first time I saw him really mad. His face was just red."

Eventually, every team in the league began to fear playing in the chicken coop.

"Other teams would come in and they kind of started laughing -- they only did it once," says LaRocque.

"People were so f--king scared of our team it was sick ... There was no tougher guys in that league than the f--king 20 guys we had on our team, I'll tell you that."

The Wexford brawl marked the first of five times police would get involved with the Quinte Hawks that season. There was the December tournament where seven cruisers were called to a brawl with the Thornhill Islanders. There was the other time a referee called the authorities because a Deseronto fan threw a glass bottle at him. And then there was the brawl to end all brawls -- the warmup fight against the Pickering Panthers.

It was Jan. 17, "Family Night" at the Deseronto Arena sponsored by Peter Boyer's Chev Olds dealership.

There wasn't a single referee on the ice and the first-place Panthers were short bodies. They had been hit by a bug. One Panther called it a case of the "Deseronto flu" -- a sudden illness that strikes a day or two before a road game in Quinte country.

The Hawks had recently traded for a goon -- "a cuckoo" as Morgan Warren calls him -- named Matt St. Amand. He was 19 and at 235 pounds he outweighed most of the teenagers by 60 pounds.

He wasn't a great puck handler or the fastest skater, but he was skilled at one thing and that's why the Hawks wanted him.

"I don't even know why he brought a stick on the ice," says Barnhardt.

Suddenly, in the middle of the warmup, the "cuckoo" skated across centre ice. The sound of a ringing cathedral bell rained down from the arena speakers, followed by the screech of AC/DC lead singer Brian Johnson.

I'm a rolling thunder, a pouring rain/I'm coming on like a hurricane

In front of all the fans, with no referees in sight, St. Amand reared back and swung his stick. It was on.

My lightning's flashing across the sky/You're only young but you're gonna die.

The Hawks swarmed the outnumbered team from Pickering. There were bloody Panther noses and fat Panther lips. The referees scrambled to get onto the ice.

You got me ringing -- Hell's Bells.

It took the rink staff about 30 minutes to clear the helmets, gloves and sticks from the ice. The Napanee Beaver published a four-column wide photo of St. Amand cocking his fist over the head of a Panther who was on all fours, trying to hide under a linesman.

The Hawks beat Pickering 7-3. They started winning all the time. They went unbeaten for 11 games shortly after Frost was brought in and they quickly moved into second place. The fans spilled out of the arena and everyone in the league was terrified of turning off Highway 401 into the "Heart of Walleye World" -- the official slogan on Deseronto's welcome road sign.

But how? How could one coach take a bunch of teenagers, mostly 16-year-olds, and the worst team in the division, and turn them into an unstoppable army?

- - -

She didn't own the hotel but she ran it like a family business. Vicki Boutilier, the manager of the Bay View Inn, lived in the two-storey, brick hotel with her husband, Leo. Her mother worked as room cleaner. She had a staff of young women -- "my girls," she says. There were never any major problems at the roadside inn, which was mostly used by fishermen.

Then Dave Frost moved in.

The deal was the team would pay for Frost and the three players to live there for the year. They each got one meal per week from the downstairs restaurant, which Boutilier also managed. They stayed in Room 22, a two-bedroom suite with a cramped kitchenette and a pullout couch. Boutilier and her husband lived in the suite next door.

Girls from Napanee District Secondary started showing up at the hotel. There were a couple regulars. One was 17 and two were 16. Boutilier's mother, JoAnne Stinchcombe, was horrified when she found condoms strewn on the nightstands and on the floor.

Enough was enough. Boutilier banned the girls from coming in after 10 p.m. but it didn't work. They contacted the boys through their upstairs window and someone would come down and let them in. In the morning, Boutilier found something, a brick or a stone, propping open the entrance door.

The league didn't like the housing situation, either. Hockey officials across the country were beginning to take a critical look at coaches and how they are screened. Out in Alberta there was a story brewing, the kind that makes parents cringe.

In November, a successful Western Hockey League coach named Graham James was charged with sexually assaulting two of his former players. Less than two months later he pleaded guilty. One of the players was Sheldon Kennedy, an NHL forward, but his name hadn't been reported because of a court-ordered publication ban. Two days after James was sentenced and Kennedy had dried the tears he wept in a Calgary courtroom, the player and his wife invited a select group of reporters to a hotel room. He was ready to tell his story because he didn't want it to happen to anyone else. He was sure there were kids out there being abused and he wanted them to have the courage to come forward.

"When you're 14 going to juniors, it's like a junior going to the pros. You're young and you're scared s--tless of life already and they just got ya ... They can do whatever they want with ya, you know?"

It had started with a sleepover at James' Winnipeg apartment and continued until Kennedy left for the NHL. He told the reporters about how he had nowhere to turn. "He had this whole thing planned. He knew what he was doing. It's the way they work. He always keeps you put down so you'd always have to look to him as the only person who could help you."

The calls for reforms and regulations were loud and clear. The Canadian Hockey League commissioned a report on what to do. There was talk of starting programs to help players speak out about the dressing room. Everyone agreed that the players needed an outlet, someone they could go to if they had a story like this. The NHL and the player's union thought they could solve the problem with a 1-800 number.

Bill Markle, the outlaw league president, was doing some thinking, too. He didn't think anything criminal was going on in Frost's hotel room, but he didn't like the optics. "I'm a parent to a lot of children. I couldn't imagine wanting my son to be in a situation where he was not with a family," he says.

The Hawks were ordered to find billets for Keefe, Barron and Tiveron, Markle says. It didn't happen.

There were rumours about Room 22 and even more gossip in the dressing room.

Only the Brampton boys knew for sure. "I was old enough to know something was going on up there and it shouldn't be going on," says Morgan Warren. "I didn't want to be a part of it. Nothing good can come of it."

Most of the Hawks never set foot in Room 22 and the rumours remained rumours.

- - -

On April 5, under a clear spring sky and in the middle of a playoff game, Dave Frost punched one of the Brampton Boys, Darryl Tiveron, in the face. Frost was charged -- and eventually given a conditional discharge -- with assault. Much was written about the punch at the time, and since Mike Danton's arrest the punch has been written about extensively. But the newspaper reports and the court files don't mention all the other times the players say Frost used violence to get results.

No one's exactly sure what game it was but Frost came into the dressing room looking for answers. He barked a question at Jefferson but the 16-year-old didn't say a word. He stared Frost in the eyes and kept his mouth shut. So, the 29-year-old man punched the boy in the face, the players say.

Jefferson's head bounced off the white, cinder block wall. Players as far away as the other side of the room heard the smack off the concrete. Barnhardt, whose spot was right next to Jefferson, felt the vibrations run down his back. Everyone sat in their stalls, frozen. "What do we do? Do we step in? It was an awkward moment for everyone," Flick says. "That's something I don't think anyone will ever forget. It was pretty sickening." Jefferson still didn't speak up. He just kept staring at Frost. "There was nothing said. I think we were all in shock," Corey Batten, one of the team's goalies, says.

The police never heard about the time Frost gave Ryan Rivard a lesson in toughness. Rivard was 15, the youngest player on the team. It was a hard year for the boy. He wasn't getting a lot of playing time and he was far away from his parents, who lived 41/2 hours away in the small town of West Lorne. His father Mike, a retired Ford assembly line worker, tried to make the drive for nearly every home game but never heard about how bad it was for his son. Even at age 24, Rivard still doesn't want to talk about it; "What's in it for me? Closure?" he asked the Citizen when the newspaper contacted him in Georgia, where he was playing in the minors. "I already have closure. It sucked."

But numerous players and the trainer say that during one intermission Frost ordered the boy to hold his bare hands out and Frost rapped his knuckles with the blade of a stick. The trainer grabbed a plastic baggie filled with snow left over from the Zamboni flood and iced the boy's knuckles.

And the police didn't haul every Hawk into the station and pry this out of them? "They didn't do anything. If the guy hits someone on the bench you'd think they'd ask all the players what was going on in the dressing room, too," Batten says.

Instead, the police stuck with one assault charge. Frost pleaded guilty and was given a conditional discharge. As long as he didn't violate his probation conditions, he wouldn't be saddled with a criminal record and could dodge the only impediment to becoming a certified NHL agent.

- - -

The teens were in and out of the bedroom, where the girl was waiting for them, at a steady pace. The ones who weren't having sex with the girl kept drinking and playing a hockey video game on a Sony PlayStation. There were about a dozen people in Room 22.

The coach denies that his players had group sex in the hotel room -- "Absolutely not" -- but some of his players say it happened.

One after another, the players entered and exited the room, Batten says. It lasted at least an hour and the girl never came out.

Up until this night no one knew what was going on in the hotel room because it wasn't open to outsiders. But with the season winding down and the teens riding high after a night of boozing, the doors were wide open.

It all started at Marty Abram's house in Napanee, just down the street from Avril Lavigne's childhood home.

As the party ended, the Brampton boys left and another group climbed into Lloyd Marks' beatup 1984 Mercury Topaz.

It was only a 10-kilometre drive to the Bay View Inn. "It sounded like a good idea at the time -- go over there and drink some more," Marks says.

Marks was so drunk he says he remembers almost nothing about the night, but he says he didn't take part. LaRocque, the team's assistant captain, doesn't recall exactly how it was organized, but by the end of the night the girl had been alone in the room with at least half a dozen boys.

She was 17, or possibly 18.

The final laughs came when LaRocque, then 19, took a piece of paper and wrote a contract. It stated that the girl had agreed to have consensual sex with the players and she and the boys signed it. It's not known if a copy of the contract still exists today.

Frost insists his players' sex lives were standard and that he wasn't involved.

"I knew there were a lot of girls, that's par for the course in junior hockey. There's no coach in North America who would be able to tell his players not to get laid."

© The Ottawa Citizen 2006